Amplified: Autistics in Conversation with Reframing Autism

Amplified: Autistics in Conversation with Reframing Autism

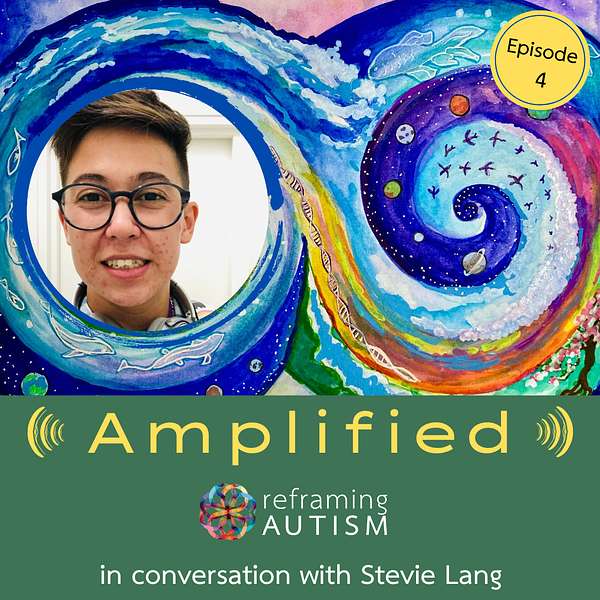

Conversation with Stevie Lang

Use Left/Right to seek, Home/End to jump to start or end. Hold shift to jump forward or backward.

In this fourth episode Ginny Grant begins by introducing the show and providing context about herself and Reframing Autism. Ginny introduces Stevie Lang, who is an Autistic trans advocate and writer. Stevie writes about Autism, gender, sexuality and relationships. They have a large, engaged Instagram following at their account @_steviewrites.

In the conversation, Stevie reflects on their late diagnosis, having discovered their Autistic identity at 28 while reading about Autism. Stevie discusses how they became involved in education and advocacy around disability and sexuality and what continues to drive their work in this. Stevie also talks about accepting their Autistic identity, their PhD, and their deep interests in relationships and queer theory. Finally, Stevie discusses their transgender expression and experience.

[Music intro: ‘Winter is here’ by Elliot Middleton for Premiumbeat, a delicate piano melody which creates a hopeful mood]

Ginny: Hello, and welcome to our fourth episode of Amplified: Autistics in conversation with Reframing Autism. I’m Ginny Grant, an Autistic advocate, a writer, and Reframing Autism’s Communications Manager.

Today, I’m so pleased to be chatting with Stevie Lang. Stevie is an Autistic trans advocate and writer. Stevie writes about Autism, gender, sexuality and relationships. They have a large, engaged Instagram following at their account @_Stevie writes. Stevie is also undertaking a PhD in Law.

For newcomers to this podcast series, Reframing Autism is an Australian-based, not-for-profit organisation which is run by and for Autistic people and their families and allies. It's dedicated to creating a world in which the Autistic community is supported to achieve acceptance, inclusion and active citizenship. And we are all about nurturing and celebrating Autistic identity.

[Music continues briefly]

Welcome to Amplified, Stevie. Let's start with your Autism journey. Could you tell us a little bit about when and how you learned that you're Autistic?

Stevie: Sure, and thank you so much for that lovely introduction, Ginny.

So I figured out that I was Autistic when I was 28, which seems to be, like, quite a common age for a lot of folks in that kind of late-diagnosed camp. But what the story behind that was for me is that I was briefly in a relationship with someone who was Autistic. And I guess I'm, like, always quite curious of the people that, you know, I'm connecting with and what their stories are and what their background is, and so they told me a bit about what it meant to them to be Autistic. And then I went and, like, did some reading about Autism, in the context of wanting to be supportive of that. But, sort of, the more they explained to me what this meant to them and the more I did research, the more it became abundantly clear that this was actually a thread in my life story that I hadn't really noticed or recognised. And so then I think like a lot of people I just went and hyper focused on Autism for, like, six months. I did lot of research, I engaged with a lot of Autistic communities online. I did actually pursue a formal diagnosis, and yeah, basically that was, that was what happened for me. So that was only two years ago now.

Ginny: So how did your interest in Autistic self-advocacy develop?

Stevie: So for me it was almost from the start, in the sense that, as I became clearer about what my Autistic experience was, and as I kind of developed more of an understanding of how profoundly that had affected me across my whole life, you know, from childhood to, especially in my teenage years and young adulthood, and just how absent the supports that I would have needed at all of those different times to have had a really different life story, and one that involved less misunderstanding and distress. Just kind of realising that those things hadn't been there for me. And that, I think like a lot of people I really experienced almost a kind of grief when I figured out that I was Autistic for the experience that I could have had if that hadn't been recognised properly and supports put in place at an, at an earlier stage. And so I think, sort of, that, that grieving process and that kind of the anger that came up around that and the, you know, the wishing for a different, a different way that things could have been was really like very quickly catalysed into, okay, well, that means that I have a role in speaking about the experiences that I've had, because it was evident that I'm not the only one. And it, it became clear to me that I had a role in talking about what would have helped, and talking about what I do need as an Autistic person. I'll also not talk too much about this but I will just mention that I’m, I'm the parent of an Autistic kid as well. And for me, that has also been something that has really made me confront and recognise the different ways that the institutions that you sort of have to engage with as a parent, like schooling, can really need help and support to move away from some of the ableist and, you know, unhelpful ways of thinking about difference and about Autistic experience. And so I guess that's something that has also contributed to that.

Ginny: Sure, sure. So, in terms of the Autistic advocacy work that you've done over the past two years, what would you say you're most proud of?

Stevie: So I’m not entirely sure how to answer this question because I think that feeling proud of something is not necessarily an emotion that I relate to too much. But what I will say is that on my Instagram I post about sexuality and sex education. And I think one of the things that I'm most glad to have been involved in is bringing Autistic experiences, and the Autistic, like an Autistic voice and Autistic needs into discussions around sexuality and consent and negotiating sexual experiences, because I think that the ways that we talk about those issues in the sex education space, sort of in the mainstream areas of that space, is not necessarily helpful to Autistic people, and I've had a lot of negative experiences in that, in, in those kinds of encounters. And I think that part of that is because I couldn't translate for me about sexuality and sexual experiences and relationships into something that actually worked within the framework that, that my mind operates in. And so I've gotten some really, I guess, heartwarming feedback from people who've engaged with the ways that I write and talk about those topics that it is really helpful to have someone who is Autistic, who has some of the same experiences as them, talking about these topics that I think it's still a bit edgy almost to talk about disability and sexuality in the same in the same breath. And so I'd say that's probably the thing that I'm most glad to be involved with.

Ginny: Yeah, absolutely. So you're currently doing a PhD in Law. Can you explain a bit more about what you're exploring in that?

Stevie: Yeah, sure. So my PhD is in the School of Law, but it's more of a gender studies or feminist theory project, looking specifically at experiences of mothers. So what my project focuses on is how judges make decisions about sentencing mothers in criminal matters. So, when a mother appears before the court in a criminal matter, and the judge or the magistrate that is assigned to that matter is making a decision about how that mother should be sentenced, there's a range of different factors that have to be considered. But none of them specifically speaks to parenting. So the way that our law is set up in, in New South Wales and across Australia more broadly, is that it's actually not a factor that should be considered when you're sentencing someone, whether or not they're a parent, but what my project is looking at is whether or not there's other ways that judges and magistrates do recognise parenting and specifically mothering when they are making decisions about whether or not to send someone to prison. And then in addition to that, I'm also looking at what the impacts of that are on mothers, particularly mothers who have been sentenced to imprisonment in the past.

Ginny: That sounds so interesting and really, really, like, valuable research.

I wanted to turn to talk about your writing a little bit. You write so beautifully, Stevie, and I think that our listeners would really appreciate hearing a little bit of your writing. So, if you don't mind, I'd like to just chat a little bit more about that.

You wrote in a post last year: “Autistic people get told in a million different little ways that our passions are too strong, our feelings are too wrong. Our bodies are too sensitive, and our minds are too complicated. Even though the way I am is different, I am loved, my contribution matters, I'm okay.” I absolutely loved that statement, and I wondered if you might talk a little bit more about how you establish a firm sense of self as an Autistic person who's facing these kinds of challenges each day?

Stevie: I think that for me the key intervention into this experience because, like so many Autistic people, I've always felt like there was something wrong. From a really young age I had this overwhelming sense that there was something about me that if the rest of the world knew about it, it was over. Like, I was, there, there was gonna be like, I didn't know what I thought was gonna happen, but it was really bad.

And I think that I never actually resolved that feeling until I did find the Autistic community. I don't think that I was actually able to get to a point where I didn't feel like there was something wrong with the way I experienced the world. Like right now, because I've got the window shut and we're doing this podcast, and I've got the fan off because we're doing the podcast, it's too hot in here so I can't think. And like, you know, I, I've always been like this, this is just how I am. This is just what my body feels like to live in, but that felt so unrelatable to what everyone else around me was saying their experience was like, and I don't think that I ever got to a point where I personally could overcome that feeling of wrongness. But what did happen was that I found other people who were like me. And I found language for talking about my experiences. And I developed the confidence to even just talk about what was happening. Like now that I've just said, “The room is too hot, I can't think”, like, already 30 per cent of the intensity of that experience is gone. Because I know that I'm talking to another Autistic person; you gave me that smile where you were like, you obviously got exactly what I'm talking about. And, you know, it just is clear that like, I'm, I'm not some kind of aberration. I'm not this unpredictable problem of a person. You know, I don't have feelings that are, that are wrong or I'm not someone who, you know, just isn't able to function in random ways. I'm an Autistic person who responds in fairly predictable Autistic ways to the things that I'm, I'm confronted with in my life. And so, for me when I find these feelings coming up now, when I start feeling like I shouldn't be feeling this way, or this is, you know, there's something wrong with me. This isn't right. To me that's usually a sign that I've drifted too far from being grounded in my Autistic experience and my Autistic community, and it's usually a sign to me that I need to connect with other Autistic people about our shared challenges, or that I just need to remind myself that this isn't because there's something wrong with me. This is because I'm Autistic. And I'm different. And so for me I think that's really been the only way of navigating this; there was never really a point at which I was able to think myself out of it without the tools that the Autistic community gave me.

Ginny: You wrote a guest blog last year for Reframing Autism called “Divergent love”, in which you described yourself as having a special interest in relationships. What do you believe makes for a healthy or successful relationship?

Stevie: It's a really tough question, because I really don't like speaking for other people, and for other people's experience. And I think that one of the things that's wrong with so much of the ways that we talk about relationships and communication in that whole world of, kind of, relationships, self-help and pop psychology discourse is that there's assumptions made there about what relationships should look like, and what communication should look like to be good relationships or good communication. And I think that anyone who has seen the way that Autistic people relate to each other will know that it's entirely possible to have relationships that look nothing like the ways that we're told they should but are deeply fulfilling and meaningful for the people in them.

I remember at a conference that I went to in Melbourne, a group of Autistic people who were at that conference all broke away and had lunch together during one of the breaks. And there were, like, times at the table where like no one was talking and everyone was just, like, stimming quietly to themselves because we had just been in a conference and it was stressful. And I just remember feeling, like, Oh my goodness, like, we were all, like, showing each other our stim toys and, like, not necessarily, like, talking about anything, you know, that we should have been talking about in that context, but it just felt so nourishing and real. It was, like, such a good way to connect with people, even though it doesn't necessarily look like, you know, how making friends might be supposed to look.

So I think that, to try and answer your question, what I would say is that a healthy relationship is someone, or a successful relationship is someone, where the people who are in it are glad to be in it most of the time. And so my approach to all of my relationships isn't to necessarily separate it out, you know, friendship and family relationships from romantic and sexual relationships; I see it all as a field of different ways of relating to the people in our lives. And each relationship is going to look different, but the way that I try and do it is based on what me and the person I'm relating to want for our connection, rather than sort of trying to put social script and assumptions about what we should be doing onto it, and I find that for me as an Autistic person that works really well. It's also a, a kind of framework within the non-monogamy community called relationship anarchy that if people are interested in that they can check out my, my profile on Instagram or there's other different places where you look that up. But for me the whole, the most liberating thing that I've done in my relationships is to recognise it's not about what it looks like from the outside, not about markers of success that people can see from the outside, it's about what does it feel like for the people who are in that connection, and how much is it making them feel like they want to be there? And I think as Autistic people, or at least as an Autistic person, that's been so important for me, because some of the ways that we're told relationships should be successful, for example, traditional forms of cohabitation or sleeping in the same bed together, or having daily communication, some of those things aren’t actually accessible to me. And so I've had to find other ways of experiencing and sharing intimacy that, that are.

Ginny: Thanks, Stevie. So much of what you just had to say about relationships rings true for me as an Autistic person, and I think there's some really, really important considerations for anyone with regard to the various relationships in their lives.

You recently wrote that “queer is the challenge to find ways of being in this harsh world, in expression of my desires, in curiosity to difference”. Can you tell us what you meant by that statement?

Stevie: Sure, I can try. I think that for me, this ongoing thread that has run through my experiences and that has been something that I've been struggling with and grappling with for at least as long as I can remember is the idea of difference and trying to come to terms with my own difference, and also trying to understand the people around me who were seeming to experience the world so differently to me. And so when I found queer theory as this undergraduate student who was very passionate about feminism, and one of my special interests is critical theory and philosophy, specifically Continental philosophy, and through kind of coming across queer theory, for me, was this way of kind of understanding and making sense of these two, like, core dynamics that have been part of my life and part of the way I think about the world for so long, which is about difference and desire. So queerness is about desire, in the sense that it's about challenging the ways that our desires are combined and mandated within heteropatriarchy. So, like, queerness is recognisable because it's different, because it's a set of desires that were, and in some cases still are, not allowed. And so for me I think what queerness means to me on this fundamental level is that it's about an expression of my desires that puts me in relationship with difference that, it's about the experience of desires that make me different. And it's also about creating space and understanding for the desires of other people that are different from mine.

Ginny: It's a great answer.

You've shared your transition journey very openly with your followers. You wrote a few months back, “I'm not fleeing a state that I hate, I'm walking towards my joy and discovering that it was possible all along.” Can you tell us a little bit about what you meant here and how this has been for you?

Stevie: Sure. I think what I was addressing there is that I certainly did and I think a lot of us do have a story about transgender experience that is all about pain. It's about the pain of, of having a wrong body or the pain of oppression and discrimination being put on you by society, and the pain of kind of this, this real distress around what previous experiences were like. And I think that, that for me, part of recognising that I am trans, and part of accepting that within myself, was recognising that I don't have to have a story that's full of tragedy and pain to be trans, that some people do have those stories, and that deserves to be given all of the space that it needs. But that's not the only way of being trans, and my story has less been about a feeling of, like, visceral disgust or distress around, around my body, or the name that I used to use, or any of those kinds of markers of that, that past experience, but it's more been a slow, and in some ways, quite difficult recognition that I actually do deserve happiness, rather than just being in a state that is tolerable. And I think for me that's, like, that's really similar to what it was like to figure out that I was Autistic, in the sense that I am a high-masking Autistic person. I, for the most part, have been able to navigate the areas of the world that I've needed to in order to survive. There's been some ways in which I've done that that have been profoundly harmful to me. But I was someone who was able to, kind of, like, get, get along, to some extent, with cost to me but I could do it, and figuring out that I was Autistic was kind of realising, like, Oh my gosh, I don't have to just be surviving. I don't have to just be, like, you know, clawing my way up this wall and, like, you know, being in a position where I'm just not falling off. Like, I can, I can feel good, like, I can have, I can, I can have ease and comfort and, like, what I need to be happy and thriving, not just, you know, alive. And I think that for me that's really similar to what it's been like for me as a trans person, is that I am not someone who had these profound and visceral experiences of dysphoria, that have, like, completely derailed the possibility of living, but I was someone who, there was nothing about the way that I was expressing myself in terms of my gender that was positive. It was just about, in a lot of ways, it was about masking, and it was about this recognition that if I performed femininity in these certain ways, more space was made for me to make mistakes socially, and it gave me this certain kind of ease of moving through the world, but other than, other than that, there was, there was nothing, there was nothing actually about me in it. It was just a way of masking, and a way of kind of surviving, and figuring out that I was trans was kind of realising, like, I can actually have joy and pleasure and happiness and I can be thriving in relation to my experiences of gender. And there's a lot of complex stuff around that because gender is a way that a lot of people are oppressed in our society and I like to be really real about that. Like, gender isn't necessarily, like, this fun and fluffy thing that we can we'll just play around with yet, because it is still used as something that that really does shape people's experiences in ways that are not okay. But recognising that I could have a gender expression and gendered experiences that felt good to me, that was, that was mind blowing. And so I think what I'm trying to get to in that little piece of writing that you just read out was that I think for me, the most significant areas of how I’ve, have come into understanding of myself have more been about recognising that I was always entitled to feel good. And that I was always able to feel good, and that the things that prevented me from feeling okay in my body and okay with myself for decades, they actually weren’t something that was inherently wrong with me. There were things that were wrong with the systems that I was given to explain and understand myself.

Ginny: Thank you so much for your time, Stevie. I just so appreciate all your insights and I'm sure our listeners will as well. And thank you to our audience for listening to this fourth episode of Amplified.

In our next episode, we'll be talking with Tigger Pritchard, an Autistic advocate, consultant and trainer from England. Please do listen in next time.

If you're not already part of our social media communities, please do join us online. You can find us on Facebook, Instagram, LinkedIn, Twitter and YouTube. We also have a website, www.reframing autism.com.au, which has a treasure trove of Autistic-created resources. Thank you and goodbye.

[Music continues]